Completing the Ironman triathlon is no small feat, yet four individuals at Newman University have successfully done just that.

The Ironman is a triathlon that takes place in various destinations throughout the world, including olympic stadiums and some of the most difficult terrains. It is organized by the World Triathlon Corp. and consists of a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bicycle ride and a 26.22-mile marathon run — raced in that order and without a break.

Jeff Lovgren

Newman Triathlon Coach Jeff Lovgren has completed three full Ironmans and 27 half Ironmans.

“It’s a part-time job,” he said. “For a full, I average up to 30 hours a week training. I am doing something very little people in the world can even imagine, let alone accomplish. It pushes me to be a better version of myself.”

To those tempted to cross off completing the Ironman from their bucket list, Lovgren has some words of wisdom.

“Never say, ‘I can’t.’ The biggest part of the Ironman race is mental,” he said. “There is a lot of time spent with only you and your thoughts, and there is a lot of doubt that can creep in. Giving up is so easy to do, but nothing worth having ever came easy.”

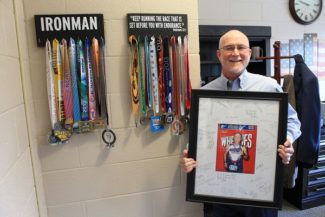

Brett Andrews

Dean of the School of Business Brett Andrews didn’t pick up endurance racing until he was 40 years old. The man who got him started on endurance racing is Brian Epperson, who was recently hired as the graduate program director for the school of business.

When Andrews first started training, it was during a time when his wife (Assistant Professor of Psychology Tammy Andrews) was heavily playing with her band and was booked every weekend.

“She was coming in from a gig about the same time I was heading out to train, so we had this high-five, ‘tag you’re it’ kind of thing as to who was watching the kids that day,” he said.

Andrews said there is no feeling quite like finishing an Ironman race.

“By the time you get to the starting line, you’ve already done it. If you’ve followed your training plan and hit all the metrics you’re supposed to hit, all you have to do next is execute,” he said.

“I feel great on race day. I’m always a little scared about what am I going to face, but by the time I get out on the course it is just phenomenal.”

Andrews received a permanent souvenir from one of his races — in the form of a nasty scar on his right arm.

Just an hour into the biking section of one of his competitions, Andrews crashed. As he was lying inside the lanes of oncoming traffic, his feet were mangled in the bike. He separated his shoulder, was bleeding badly down his legs and was run over twice by riders behind him. Luckily, he was pulled to safety by a volunteer who happened to be standing nearby.

“At that point I realized, my body will take this,” Andrews said. “I thought, ‘I just trained for a year for this race … am I really out of it?’”

To his surprise, the bike still worked. Andrews still had 96 miles left to go, so he decided to get back up and keep going.

“My wife saw me coming out of the bike leg and I told her I crashed while showing her my torn jersey and the blood all down my back. She got quiet for a moment and asked, ‘Well, can you still run?’ and I said ‘Yeah, I guess so,’ and she said, ‘Well rub some dirt on it and get back in the game. Go finish.’”

“It was kind of mean,” Andrews said with a laugh. “So I took off. Later her friends asked her why she was kind of mean about it and she said, ‘Oh no, he was just looking for permission to quit and I wasn’t going to let him do that.’ She’s a psychologist — she gets it.”

Andrews explained that everyone is faced with personal limits at one point or another. Some push themselves physically, others push themselves mentally in academics, for example.

“What happens in an Ironman is only a few hours. What happens in your college career might take four to six years, but you eventually get to the finish line, which is graduation. And you get to look back saying, ‘This is an accomplishment that I did that nobody can take away from me. And yes, I had help. Maybe I needed a tutor in this class, or I needed to take this class over here and transfer back in.’ It doesn’t matter. Did you get to the finish line and did you accomplish it?

“Unless you challenge yourself, you’ll never figure out your limits,” Andrews added. “And for some people, there is no limit.”

Before Newman interviewed senior Brandon Steiner about his recent and first-ever Ironman experience, Andrews had a few words to share.

“I don’t know Brandon Steiner, but I could tell you a little about him. Nobody sees all the work he puts in, or all the days that he forces himself to not eat what he’d like to eat. Nobody sees all the days he gets up at 4 o’clock in the morning every single day to do laps, to pound miles, to get on the bike, whether it’s on the trainer or on the road. Nobody sees the lack of a social life, the difficulties dealing with lack of sleep. Nobody feels the pain that your body is racked with as you train for something across all three sports.

“I have immense amounts of respect for anyone who’s done a half iron or iron because it is a difficult lift on a good day,” Andrews continued. “It’s hard. We don’t do triathlon simply because we want to have a wreck or get up earlier and be racked with pain. It’s because it makes us better athletes and better individuals. We take that success that we have and we now have a pattern for the rest of life where we know what it takes to invest ourselves toward a goal, even when faced with setbacks.”

Brandon Steiner

This summer, Brandon Steiner, a senior member and team captain of the Newman triathlon team, completed the 70.3-mile half-Ironman in Boulder, Colorado.

He competed on his own but trained with both of his triathlon coaches’ adult teams throughout the summer. His two coaches, sister and eight other friends traveled to the race to support Steiner as he competed.

Steiner said that, for him, the most difficult aspect of the race was knowing his “why.”

“For Newman, there are scholarships that motivate you to compete (in triathlon), but for this, I was paying and it costs $325 just to enter,” he said. “It was the most amazing race of my life and they do a great job of setting it up, but I did have to ask myself, ‘Why am I paying this much to do it, driving all the way to Boulder and staying for five days? Why do I get up to bike 70 miles on my Saturday morning, give up my Friday night nightlife and sacrifice so much to be able to train for it?”

Steiner said he never imagined that he would compete in an Ironman competition prior to his college career.

“It wasn’t on my mind or radar, but then I thought why not? You only live once, and I’m not going to get any fitter,” he said.

“You put in the effort, you’d reap the rewards. It takes time to build to that level of endurance. I know guys who are bigger and heavier and older than me doing it double my speed, and it’s pretty amazing. There’s an amazing amount of talent and energy, unlike anything I’ve ever experienced.

“It was the closest I’ll ever get to the Olympics,” Steiner continued. “The feelings you get and the number of athletes and supporters there are was well worth the money spent, which is hard to say when you’re a broke college student.”

Steiner finished his first half Ironman with a time of 6:03:21. He took 740th place overall out of the 2,166 competitors who finished the race. Although his only goal was to finish the race, Steiner said he may aim for a specific time and place the next time he races.

“I’ve invested a lot in myself through it, and it’s really what has made me the person I am today, in a way,” he said. “I grew up a lot by having to organize my life according to how I train. It’s a lifestyle at this point, it’s not a hobby.”

If he has the time and resources available, Steiner said he’d like to try for a full Ironman in the future.

“The cost of the race is probably the largest barrier for me, so if anyone wants to sponsor me, I’ll put your brand on my bike,” he said with a laugh.

J.V. Johnston

As part of his training, Steiner biked alongside Vice President for University Advancement J.V. Johnston every Wednesday leading up to their races.

“At first, Brandon couldn’t keep up with me, and at the end, I couldn’t keep up with him,” Johnston said.

Johnston has completed seven half Ironman races.

“There was a very stressful episode in my life where I decided that I needed to do something, or I wasn’t going to make it,” Johnston said.

Johnston had not swam for 40 or so years when he decided to make a visit to the YMCA. He was the only one in the 25-yard long lap pool and was five yards from the end when he suddenly thought he was going to drown.

“I can’t make it,” Johnston thought. “I either had to call the lifeguard to save me or grab the rope. I grabbed the rope, pulled myself to the end, got out of the pool and I was just depressed. I went home and said, ‘Nope, I’m going to do it. I’m going to swim and do this upcoming triathlon event at the Y.

“So I did and that’s how I kind of got hooked,” Johnston said. “The feeling after — that sense of accomplishment — is something you can’t describe.”

When a person trains for an Ironman race, they have to experiment with what works for them as an individual, Johnston explained.

“It’s like master planning for five months, and then you get to race day and have to make sure you do it,” he said. “You start listening to your body a lot, and you’re essentially competing against yourself. To get the best time you can, you must determine which pace you have to go to perform 85 to 90 percent of your maximum pace and sustain that for hopefully less than 6 hours.”

The average Ironman race will strip the human body of around 7,500 calories, yet the body only carries an average of about 2,000 calories in the glycogen and the liver. So how does one make up the difference?

“A good coach is worth every penny you spend on them,” Johnstons added. “Having a coach helps you to not make the mistakes of everybody else before you. It’s not just about buying a training plan and doing that, it’s actually having someone you can talk to, that you can parse the data with after you come back from a long ride because it’s so much more than just swim, bike, run.”

The Ironman is considered the toughest one-day endurance event on the planet, and the atmosphere of the race itself is simply “something else,” Johnston said.

“Imagine 2,500 people, all with swim caps on, who are waiting to go into the water. There is also a football field full of bikes — all a foot apart, going both directions on each rack and the value of the bikes ranges from $200 to $15,000.

“You’re racing against your age group and you’re trying to do well, but everybody roots for everybody else because they know that just to finish is quite an accomplishment,” Johnston said.

Andrews agreed and added, “The workers and volunteers provide better race support and more care for the athletes than any other race I’ve ever been a part of. It’s really a tribe of people. I also love the fact that Ironman is the only athletic activity where the professional athletes and the amateurs run together at the same time on the same race course.”

To anyone who hopes to one day compete in an Ironman race, Johnston shared his advice.

There are four basic race distances: Sprint, Olympic, half Ironman (70.3) and the full Ironman (140.6).

“Start off with sprints and make sure you do an Olympic,” Johnston said. “Then either get a coach if you can afford one, or if you can’t, there’s lots of literature online and training programs available. Also talk to other athletes that have done it, as they’d be more than happy to talk to you for hours and give you advice.”